From the palliative care ward to an MD-PhD

“Healthy” diet

I was raised in a medical family. Both my parents are M.D. Ph.D.s and health was always the topic of discussion around the dinner table. Logically, you might think that I ate a healthy diet growing up. At the time, both my parents thought I ate reasonably too. But what was reasonable? When I was in middle school, a typical day of eating for me looked like this:

- Breakfast was half a box of Special K Red Berries cereal with skim milk and a banana. (Net carb counter = 270 grams)

- At school, there were usually munchkin donuts in homeroom, and everyone partook. I liked the raspberry jelly! (Net carb counter = 297 grams)

- Lunch was pizza and French fries with a cookie. Even a twelve-year-old knows this isn’t healthy, so I did my best to offset my indulgence with vitamin C-rich fruit snacks and grape juice. (Net carb counter = 503 grams)

- After school, I’d finish my cereal box from the morning to charge me up with “healthy” whole grains for soccer practice. (Net carb counter = 743 grams)

- I’d run around for an hour and get “lots” of exercise, earning myself a nice healthy fish dinner! My dad would pick me up and we’d go to Subway. Eat Fresh! I’d get the tuna salad sandwich, which was rich in Omega-3s. I heard about those because I was so medically informed. I even knew that the mayonnaise used to make the tuna salad was made with soybean oil! Soybeans, a healthy vegetable! I’d also get it with all the veggies on top! (Net carb counter = 888 grams)

- Finally, I’d wind my day down with a pre-bed snack of fruit. I kept a nightstand filled with Ocean Spray orange-flavored Craisins, and would have one whole four-serving package to put me to sleep. (Net carb counter = 1 kilogram)

The next day, I wake up and do it all over again.

I wasn’t fat, so I was healthy

If you’re reading this, you’re certainly more nutritionally informed than I was in middle school through college. So, you might guess I was an obese child. Not in the slightest. But my genetic resistance to obesity only reinforced that the “healthy” diet I was eating was good for me. I was skinny, so I was healthy. This fact was continually reinforced by my parents and my entire social ecosystem. If nothing else, I was genetically gifted – just one of those lucky ones to remain thin in that food environment.

Running down my luck

I excelled at school and sports. I was always at the top of my class and kicked butt at just about every athletic endeavor at which I directed my body and mind. Winning my division in half marathons and marathons was no problem for me. By seventeen I could cruise a half marathon in seventy-five minutes. By twenty-two I was an Ivy League valedictorian.

My body and brain were firing on all cylinders, fueled by a “well-balanced” diet. By this point, you’d probably guess I was an arrogant, privileged youth who could use a dose of humility, especially because I had my eyes set on becoming a doctor curing the world’s ills with my knowledge. Don’t worry, I got what was coming to me when my health inevitably crumbled.

Scary diagnosis, times 2

My first strike came with a strange diagnosis. Despite my high calcium intake, weight-bearing exercise routine, and lack of a family history, I developed severe osteoporosis. My bones were, biologically, about seventy years old and I had fractures from my feet to my shins to my femurs to my spine. After a thorough workup by some of the world’s best orthopedists and endocrinologists, I was saddled with a “diagnosis of exclusion”: relative energy deficiency syndrome (RED-S). The treatment for RED-S is more calories.

Ironically, I was treated as if I were anorexic and encouraged to address my medically perceived eating disorder. Ashamed to the world, and disgusted with myself for hurting my body by not eating enough, I complied with medical advice. I ate ice cream and fudge and other calorie-dense foods at least five times a day to address my RED-S. I wanted to prove that I wasn’t pseudo-anorexic and determined to fix my bones. Surprise! It didn’t work.

My second strike came in the form of stomach aches, the likes of which I had never experienced. At the end of college, I developed ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease. Osteoporosis might have stolen running from me, but colitis stole more. Food became a chore and socializing became a terror. Even sitting in lecture, I would become anxious when I felt a grumble. Is this a bleed? Am I going to need to embarrassingly rush to the bathroom flashing my tail lights red for the whole building to see?

I’ll certainly never forget the morning of my graduation. I was the student speaker at the ceremony, scheduled to speak following our guest speaker (a professional comedian) and the president of the university. I ate nothing the previous night and, that morning, I woke up at 3:30 am to vacate my bowels with an enema to ensure I wouldn’t have an episode in front of 11,000 people and on camera. Nevertheless, as I walked the podium, I felt a gurgle. There was some pain, but it subsided. After the ceremony, I went to the bathroom and there was a dribble of blood. I imagined what might have happened during the ceremony if I didn’t fast and empty out with the enema.

Medications didn’t help

Nevertheless, I remained optimistic that one of the drugs that was being prescribed to me would solve my problems. None did, and several even made me worse. I remember, on one occasion, convulsing in pain on the floor of my dorm for twenty-four sleepless hours as the smooth muscles of my bowels contracted against sphincters that had sealed shut as a result of the same medication. As my bladder filled too, but I could not pee, I genuinely considered using a straw stolen from the dining hall as a make-shift urinary catheter. Environmental concerns aside, I still can’t use a plastic straw.

It got worse

My conditions progressed until they reached an unfortunate climax. Strike three came and I was out. Within a month of my move to Oxford, England to begin my Ph.D. studies, I had the worst colitis flare of my life. I dropped 20% of my body weight in three weeks and I ended up in the palliative care ward of a British National Health Service hospital. For three days, my heart rate remained in the twenties. I was so fragile and feeble that my mother and I darkly joked and celebrated when a cute nurse walked into the room and my heart rate temporarily hit 30 beats per minute. That’s the only photograph and positive memory I have from that time.

I thought I might die.

After three days of being poked and prodded, I was diagnosed with turmeric poisoning. Yes, my doctors told me I had consumed too much of turmeric’s active component, curcumin. It was an absurd proposition, even independent of the fact that the half-life of curcumin is about half a day and I hadn’t had any for the six half-lives that I was in that palliative care ward.

But I was only too happy to be discharged because, finally, my confidence that the system would fix me was depleted. I just wanted my own bed (and away from all the beeps, buzzing, and demented screams that harassed me in that ward). I waddled out of palliative care with a heart rate still in the twenties and then lay in bed for days. My only company was some fluid nutrition and a resignation that my life would either end or, maybe worse, perpetually suck.

Last ditch attempt, a ketogenic diet

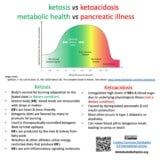

Evidently, I didn’t die. Time passed and I gained back some energy. I decided it was finally time to use my own intellectual resources to – excuse the pun – figure this shit out! Like so many people I’ve since met, desperation roughly shoved me into the solution. After some self-study, I sought out the support of a doctor, Vyvyane Loh, who was the first person to give me permission to consider that a ketogenic diet wasn’t crazy. With her support, both medical and emotional, I set out on what I was still sure was a stupid idea: I cut out all carbs and started to eat fat like there was no tomorrow.

What happened next blew my mind. Within just one week, my ketogenic diet had caused my symptoms to disappear and decreased my colitis inflammation marker (calprotectin) from 150 ug/mg to 20 ug/mg. I also felt incredible! I had so much energy and my brain felt back online for the first time in over a year. As weeks turned into months, I came off my medications and my symptoms and inflammation remained at bay. By the one-year mark of my ketogenic diet, I checked my bone density and was further shocked to discover that my bones had recovered faster in that year than they had on any medication previously. In fact, I no longer had osteoporosis. It’s not an exaggeration to say that addressing my metabolic health through nutrition may have saved my life.

My health is restored

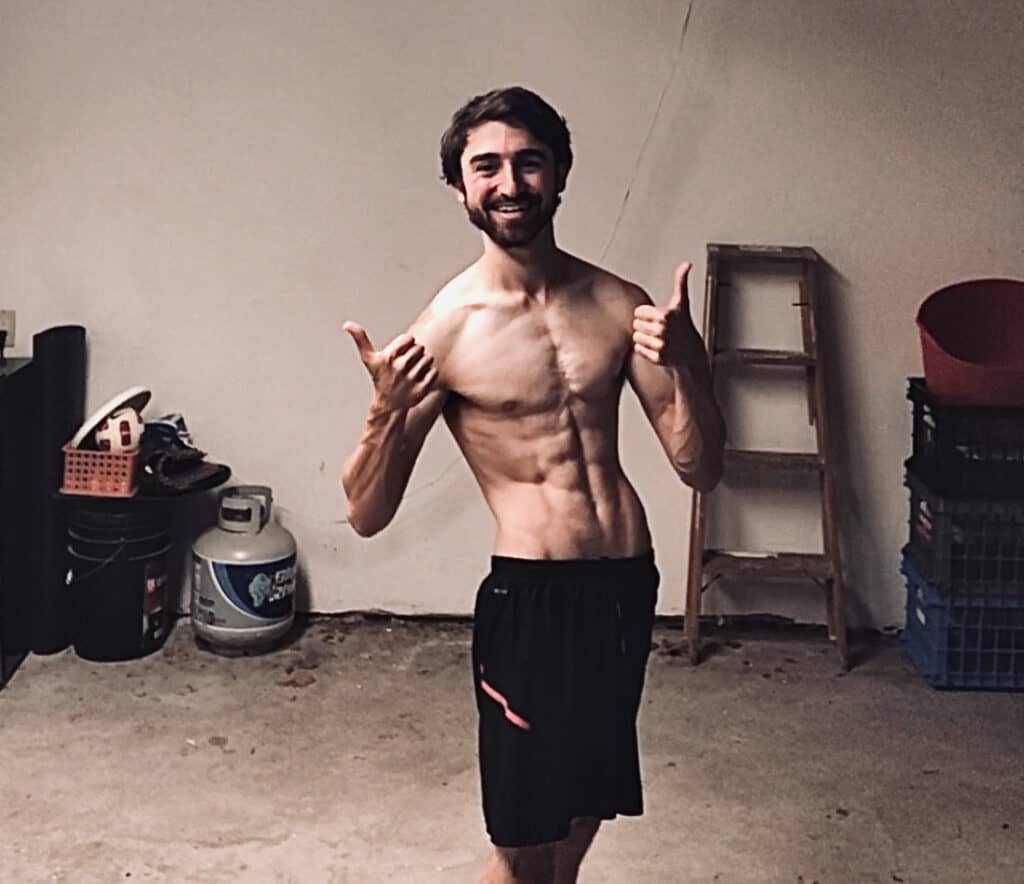

So, where am I now? At the time of this writing (September 2020), I’m just one month away from defending my Oxford Ph.D. thesis on Ketogenics and Neurodegenerative disease, and nine months away from starting at Harvard Medical School. I’m enjoying athletics once again and even got my six-pack back! Sometimes I look in the mirror (admittedly with a degree of vanity) and reflect on the fact that I can now do 30 one-arm pushups, compared to only a couple of years ago when a heart rate of 30 beats per minute was my physical best.

I live my life as a series of n = 1 experiments and treat nutrition like a never-ending quest of personal improvement. It’s fun! Food is now both an intellectual pleasure and a gastronomic one. My mission from this day until the day I die (at the ripe old age of 200) is to teach people and the healthcare system that nutrition is health, and health is everything.

More from Dr. Nick Norwitz, PhD, MHP, medical student

Success stories from the our team

- Metabolic Multipliers

- Captain Malagon

- Cecile’s

- Nurse Christie – My mother’s suffering spurred me to find keto